“Let me forget about today until tomorrow,” Bob Dylan wrote one day in the opening stages of 1964. It was the final line of a song filled with lines — some poignant, some instructive, somewhat perplexing in the aggregate.

From our vantage point today, it is tomorrow and thus the perfect time to remember this highly influential song, this oft-interpreted, oft-covered, oft-awarded song that may or may not have been inspired by a man with a big tambourine.

“Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me,” sang Dylan then, and before you could say Bob is Bob spelled backward everyone seemed to be singing it. In 1965, the year Dylan recorded it, 13 others did too. Judy Collins, Stevie Wonder, Melanie, Odetta, The Four Seasons, Glen Campbell (an instrumental), Joni Mitchell, Johnny Rivers, Gene Clark (The Byrds singer put a mid-’80s soft rock twist to it), Crowded House, The Charlie Daniels Band, and Mountain are iceberg tips on a long list of folks who have taken a shot at Dylan’s masterpiece at one point or another.

But it was an unknown Los Angeles band co-opting Dylan for their first hello who made the biggest noise with their version of it. Because what Bill Haley & His Comets had done with “Rock Around the Clock” in the mid-’50s and Nirvana would do with “Smells Like Teen Spirit” in the early ’90s, newbies The Byrds did with “Mr. Tambourine Man”: they kickstarted a new music genre.

Dylan started writing “Mr. Tambourine Man” after he and some pals experienced Mardi Gras on a February ’64 trip to New Orleans. Author Nigel Williamson, in The Rough Guide to Bob Dylan, pictured Mardi Gras in the song’s swirling and fanciful imagery. Some will tell you they hear French poet Arthur Rimbaud in the words, and Dylan himself has acknowledged the song’s nod to Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini’s La Strada.

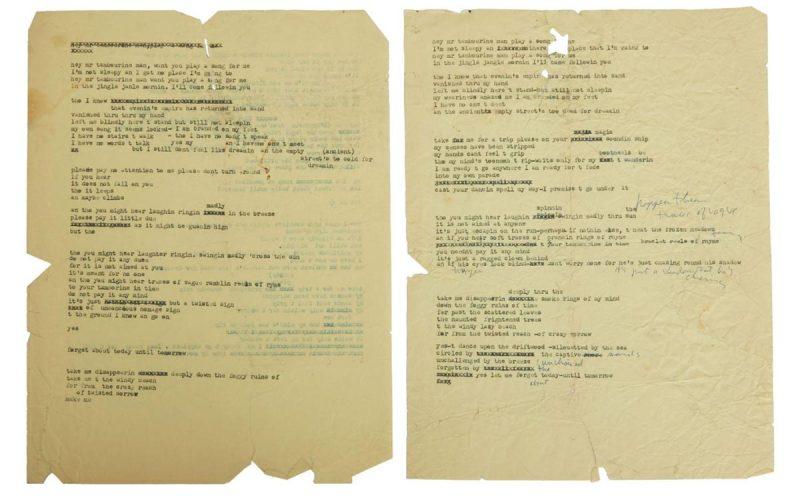

Dylan took his first shot at recording “Mr. Tambourine Man” in June 1964, with producer Tom Wilson at the desk and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott harmonizing. Seven months later, with Wilson overseeing the final Bringing It All Back Home session on January 15, 1965, Dylan re-recorded it. After trying it with drummer Bobby Gregg playing a tambourine-heavy 2/4 rhythm, Dylan and Wilson settled on a version with only electric guitarist Bruce Langhorne accompanying.

Five days later, on January 20, 1965, The Byrds recorded “Mr. Tambourine Man” at Columbia Studios in Hollywood.

Shortly after Dylan first recorded “Mr. Tambourine Man,” three veterans of the early ’60s L.A. folk circuit — Jim (later Roger) McGuinn, Gene Clark, and David Crosby — formed The Jet Set and expanded on what McGuinn was already doing: a fusion of folk-based lyrics and melodies arranged like The Beatles.

In August 1964, says GoldRadioUK.com, The Jet Set’s manager, Jim Dickson, got his hands on a copy of Dylan’s shelved demo with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. But it wasn’t love at first listen. McGuinn, Clark, and Crosby were underwhelmed by “Mr. Tambourine Man” until McGuinn changed the time signature from Dylan’s 2/4 to a more standard 4/4. They soon worked up their own version of the song into an arrangement much like we know today, albeit with a short-lived marching band drum driving it.

Even before Dylan recorded his final version, manager Dickson invited him to a Jet Set rehearsal to hear their rendition. The song’s writer was duly impressed. “Wow, you can dance to that!” Dylan has said.

Dylan’s version is a sprawling five-and-a-half minutes with four verses, but The Byrds (as The Jet Set dubbed themselves in November of ’64 when bassist Chris Hillman and drummer Michael Clarke were added) opted to play the radio game by keeping their recording under three minutes; thus, only the song’s second verse and two repeats of the chorus are on The Byrds’ recording.

Backstage Access:

Laurel Canyon, The Byrds, Elvis Costello and My Rickenbacker Guitar

When The Byrds hit the studio on that January day in 1965, 23-year-old singer/guitarist Crosby was the old man of The Byrds; the other singer/guitarists, McGuinn and Clark, were 22 and 20, respectively, while the newcomers, Hillman (20) and Clarke (18), were the youngest.

Armed with McGuinn’s 12-string Rickenbacker guitar and the tight vocal layers of McGuinn, Clark, and Crosby, the sessions had an unfamiliar vibe. Like many other young bands of that time, The Byrds got overruled by a producer (in this case, Terry Melcher) who preferred the steady predictability of session players in the studio over the band itself. Thinking the young players still needed time to gel musically, Melcher kept the band on the sidelines for “Mr. Tambourine Man,” so only McGuinn played on it. Backing his 12-string was rhythm guitarist Jerry Cole, bassist Larry Knechtel, Leon Russell on electric piano, and drummer Hal Blaine, all from the L.A. collective of top session musicians known as The Wrecking Crew. By the time recording for their debut album began a couple of months later The Byrds were ready to play their own instruments.

The Byrds introduced themselves with “Mr. Tambourine Man” on April 12, 1965, just three weeks after Dylan’s version first appeared on his Bringing It All Back Home album. The Byrds reached #1 on both the Billboard Hot 100 chart and on the UK Singles Chart, giving these L.A. upstarts the first-ever #1 recording of a Bob Dylan song. They had helped their cause by taking Dylan’s song in more of a Beatles direction, giving his lyrics an electric rock band treatment, effectively creating the musical subgenre of folk rock in doing so.

And people noticed.

The instant success that The Byrds had with “Mr. Tambourine Man” ignited a wave of folk-rock songs in the mid-’60s, with bands and singers on either side of the Atlantic Ocean offering their own take on McGuinn’s jingle-jangle guitar sound coupled with folk music’s intellectual qualities. While this hybrid had been previously discouraged by purists in the U.S. folk community — think how Dylan was treated for going electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival — it also predated The Byrds, with The Animals in ’64 doing a rocked-up rendition of the traditional folk song “The House of the Rising Sun,” for example, and George Harrison’s 12-string guitar on Beatles’ recordings.

George Harrison: 20 Essential Songs

But it was the commercial success of The Byrds’ version of “Mr. Tambourine Man” and their debut album of the same name that created a template for folk rock that proved successful for many acts to follow. Even Dylan was at least somewhat influenced to use electric instrumentation after he heard The Jet Set’s rehearsal that day.

Soon The Byrds’ new sound could be heard in recordings by other Los Angeles-based acts, like The Turtles, The Mamas & The Papas, The Grass Roots, Barry McGuire, and Sonny & Cher, and in recordings by The Lovin’ Spoonful and Simon & Garfunkel. And more than one rock music scribe has noted that this influence continued for decades as The Byrds’ folk-rock sound showed up in the music of Big Star, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, R.E.M., The Bangles, and more.

The Byrds’ first hurrah had given rise to a new form of music and engendered the term folk rock as the U.S. music press in the summer of ’65 coined the phrase to describe their sound.

The lyrics have baffled many courageous enough to interpret it. Is it a paean to psychedelic drugs? A cry out to the muse? Do Dylan’s words reflect his audience’s demands on him? Are the lyrics religious? Do they sing of Jesus, or perhaps the Pied Piper of Hamelin?

One scene in the 1995 Michelle Pfeiffer flick Dangerous Minds opined that “Mr. Tambourine Man” was indeed about drugs, but for what it’s worth Dylan says it isn’t.

Over the years Dylan’s and The Byrds’ versions of “Mr. Tambourine Man” have appeared on various greatest-songs-of-all-time lists. Both versions appear on Rolling Stone’s 2004, 2010, and 2021 lists of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time; The Byrds were listed at #79 initially, before dropping to #230 in 2021, while Dylan’s version was first ranked #106 (#164 in 2021).

Each version has been honored with a Grammy Hall of Fame Award, and in 1999 National Public Radio listed The Byrds’ version as one of the 300 most important American records of the 20th century.

So, what’s it all about? Are any of the interpretations mentioned above, correct? Well, in 1985 Dylan maintained that guitar player Langhorne inspired it. “He had this gigantic tambourine,” Rolling Stone reported Dylan as remembering. “It was as big as a wagon wheel. He was playing, and this vision of him playing this tambourine just stuck in my mind.”

Classic Rock Landmarks: Like a Rolling Stone

Photo credit: KRLA Beat, public domain