“He not busy being born, is busy dying.”

There it was, hiding in plain view in one of Bob Dylan’s most memorable lyrics, released in the spring of 1965.

“He not busy being born, is busy dying.”

Dylan, 23 and a firmly established toast of the thriving folk scene, laid it all out there: stagnation equals death.

Taken in tandem with the electric arrangements on his still fresh Bringing It All Back Home album, that declaration from “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” properly presaged “Like a Rolling Stone.” And yet Dylan’s six-plus-minute, organ-driven diatribe blindsided the folksters, the hipsters, the popsters, the hippies, the tuned in, the turned on, and the skinny-tie-wearing record label intelligentsia alike when it landed in July of 1965. But while “Like a Rolling Stone” dressed itself up as an unwelcome foray into commercialism to the folk crowd that had adored Dylan, it offered in trade an exclusive lifetime seat among rock & roll royalty.

How does it feel?

With “Like a Rolling Stone,” Bob Dylan became a sudden and unexpected toast of a different crowd, in the process dispensing one of the most surprising and paradigm-altering compositions in the rock era. “Dylan had been famous, had been the center of attention, for a long time,” wrote Crawdaddy! founder Paul Williams in his 1991 book, Bob Dylan: Performing Artist the Early Years 1960-1973. “But now the ante was being upped again. He’d become a pop star as well as a folk star…and was, even more than The Beatles, a public symbol of the vast cultural, political, generational changes taking place in the United States and Europe. He was perceived as, and in many ways functioned as, a leader.”

In the spring of 1965, after coming off tour Dylan was toast and not really digging his direction; he later revealed that his career was on the chopping block.

“Last spring, I guess I was going to quit singing,” he told Playboy in 1966. “I was very drained, and the way things were going, it was a very draggy situation.”

And then something happened to turn it all around, he told Playboy. “‘Like a Rolling Stone’ changed it all; I didn’t care anymore after that about writing books or poems or whatever. I mean it was something that I myself could dig. It’s very tiring having other people tell you how much they dig you if you yourself don’t dig you.”

How does it feel?

In barely four years, Bob Dylan — born Robert Zimmerman in Hibbing, Minnesota — had gone from New York City couch-surfer and infrequent folk singer in Greenwich Village to wowing the folk traditionalists at the Newport Folk Festival and being invited to sing at the March on Washington ahead of Martin Luther King Jr’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. The former teenage runaway and college dropout who’d thumbed his way east to pay an unannounced visit to his hospital-bound hero Woody Guthrie had turned a wing and a prayer into folk stardom. At 19, he’d known how it felt to be called “a significant new voice on the folk horizon” by the New York Times; at 22, his “Blowin’ in the Wind” had been a #2 pop single and double-Grammy winner for Peter, Paul & Mary; and at 24 he’d become a musical phenomenon and influencer. A voice of his generation. And he was ready to cash it all in.

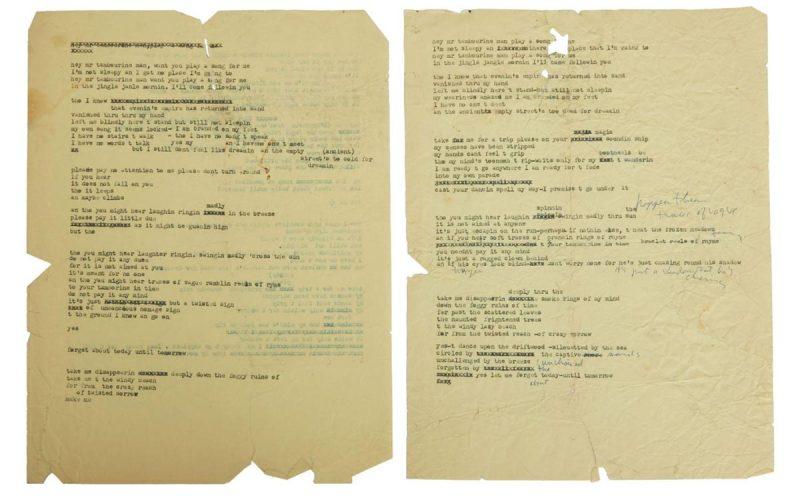

And then came “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan was constantly in front of a typewriter in ’65, writing anything and everything. In that context, out came what he called a long piece of “vomit” (10 pages of it, maybe 20, depending on who he told). He’d “never written anything like that before,” he said.

“It wasn’t called anything,” Dylan told the Saturday Evening Post, “[it was] just a rhythm thing on paper all about my steady hatred directed at some point that was honest. In the end it wasn’t hatred, it was telling someone something they didn’t know, telling them they were lucky. Revenge, that’s a better word. I had never thought of it as a song, until one day I was at the piano, and on the paper it was singing, ‘How does it feel?’ in a slow-motion pace, in the utmost of slow motion following something.”

How does it feel?

On June 15th and 16th, 1965, just weeks after Dylan whittled all those words down to the final lyric, “Like a Rolling Stone” was recorded in Studio A of Columbia Records in New York City. Producer Tom Wilson, who had helmed Dylan’s previous four albums, was at the desk for “Rolling Stone.” It turned out to be his final time working with Dylan.

Things didn’t go all that smoothly on the first day of recording, with Dylan and crew struggling to find what you might call the essence of the song in 3/4 waltz time.

Everything fell into place the next day when Dylan moved from piano to guitar and the band switched to a rock & roll 4/4 signature, and when a 21-year-old session guitarist named Al Kooper bravely took the Hammond B-2 organ for a spin. Kooper, who was only in the studio as a guest of producer Wilson, wasn’t supposed to play on the track, but there he was, young and just full of himself enough to think he could sneak his way into one of the most important rock recording sessions ever. First, he grabbed his guitar before quickly realizing he was way out of his league with blues guitar legend Mike Bloomfield, who Dylan personally recruited to play on “Like a Rolling Stone.” So, instead Kooper sat down at the organ and because no one told him not to he faked his way through that organ line that became as recognizable as any organ line in history. When Dylan heard it, he insisted that Wilson bring Kooper’s handiwork up in the mix. Kooper, notably, would go on to help launch Blood, Sweat & Tears and later produce Lynyrd Skynyrd’s first three albums.

They did 15 takes of “Like a Rolling Stone” on June 16th, though Wilson was convinced that their fourth take was the winner. He was right; it was that take that wound up on Highway 61 Revisited.

Released as a non sequitur of a single on July 20, 1965, “Like a Rolling Stone” defied all logic relative to other singles of the day. Love songs ruled the charts, this song expressed bitterness and resentment. Three minutes max was the rule of the day for radio airplay, this song was just hitting its stride at three minutes. The storyline, if you could call it that, centered on the vague “Miss Lonely” and a weird cast of characters (jugglers and clowns, Napoleon in rags, a chrome horse, a diplomat with a Siamese cat). Pundits pondered, pontificated, and opined on these details, as pundits are wont to do. Was Miss Lonely model/actress Edie Sedgwick? Was it Joan Baez? Marianne Faithfull? Dylan himself perhaps offered a clue when, after his 1966 motorcycle accident, he noted that “when I used words like ‘he’ and ‘it’ and ‘they,’ and talking about other people, I was really talking about nobody but me.”

In what is a bit of a recurring theme amongst so many of the great rock songs, “Like a Rolling Stone” was nearly never released as a single. Columbia Records recognized how it rubbed against the grain, so it was initially rejected for singlehood. But Shaun Considine, a release coordinator for Columbia back then, secretly took a copy of it to a new Manhattan club called Arthur and asked the DJ to give it a spin.

How does it feel?

The crowd loved it and insisted that it get played repeatedly that night. Columbia execs walked in the next morning to requests for copies from a radio DJ and a program director from NYC’s leading pop radio stations. Before you could say Bob is Bob spelled backward, “Like a Rolling Stone” was a single.

Despite all the reasons that it shouldn’t have worked, “Like a Rolling Stone” quickly sold a million copies and climbed the all-important Billboard pop chart to #2 (wedged between The Beatles’ “Help!” at #1 and The Beach Boys’ “California Girls” at #3).

Five days after its release, Bob Dylan played “Like a Rolling Stone” live for the first time at the Newport Folk Festival in Newport, Rhode Island. It was also his first public plugging in, and the Newport folk purists were not amused. As guitarist Bloomfield remembered, this rock & roll they were force feeding to the folksters was popular amongst “greasers, heads, dancers, people who got drunk and boogied.”

How did it feel?

“I was kind of stunned,” Dylan said in that 1966 Playboy interview. “But I can’t put anybody down for coming and booing; after all, they paid to get in. They could have been maybe a little quieter and not so persistent, though.” And so, in July of 1965, Dylan shed his folk ways in favor of rock & roll digs, but it was never his intention to cast anyone aside. “Contrary to what some scary people think, I don’t play with a band now for any kind of propaganda-type or commercial-type reasons. It’s just that my songs are pictures and the band makes the sound of the pictures.”

Bob Dylan – Like a Rolling Stone (Live at Newport 1965)

Nearly 60 years on, “Like a Rolling Stone” remains rock royalty. “No other pop song has so thoroughly challenged and transformed the commercial laws and artistic conventions of its time, for all time,” said Rolling Stone magazine (which took its name partly from Dylan’s song). Paul McCartney, who had recorded “Yesterday” just a month before Dylan laid down “Like a Rolling Stone,” called the song “beautiful,” and said that Dylan “showed all of us that it was possible to go a little further.”

Bruce Springsteen, who once wore the “new Bob Dylan” tag, was 15 when he first heard the former Mr. Zimmerman’s master work. “On came that snare shot that sounded like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind,” he recounted while inducting Dylan into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988. “The way that Elvis freed your body, Dylan freed your mind, and showed us that because the music was physical did not mean it was anti-intellect. He had the vision and talent to make a pop song so that it contained the whole world. He invented a new way a pop singer could sound, broke through the limitations of what a recording could achieve, and he changed the face of rock & roll forever and ever.”

Dylan offered his own assessment shortly after he’d recorded “Like a Rolling Stone”: “I wrote it. I didn’t fail. It was straight.”