I recently saw Once We Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band, in a theater, and given the givens, I hope it will be placed on one of the TV streaming services soon. I know it’s due to air on Canada’s Crave network but not sure when.

I feel funny writing a blog without first acknowledging what we are all going through together trying to stem off the Coronavirus. I have some of my own thoughts, positive even in the face of all this, that I will share with you at the end of this review.

I left the movie theater feeling weird. Something, or some things, just didn’t feel right about this film. Not that you shouldn’t see it… you should. Some parts are incredibly fascinating, there’s some very important history here that needed to be documented, and I learned a lot. But, even before the movie started, I was wondering why the title of this film was, Once We Were Brothers: “Robbie Robertson” and The Band?

The film is inspired by Robertson’s autobiography, Testimony: A Memoir. So fair enough, I guess we should be ready for this documentary to be about Robertson’s life and his take on The Band.

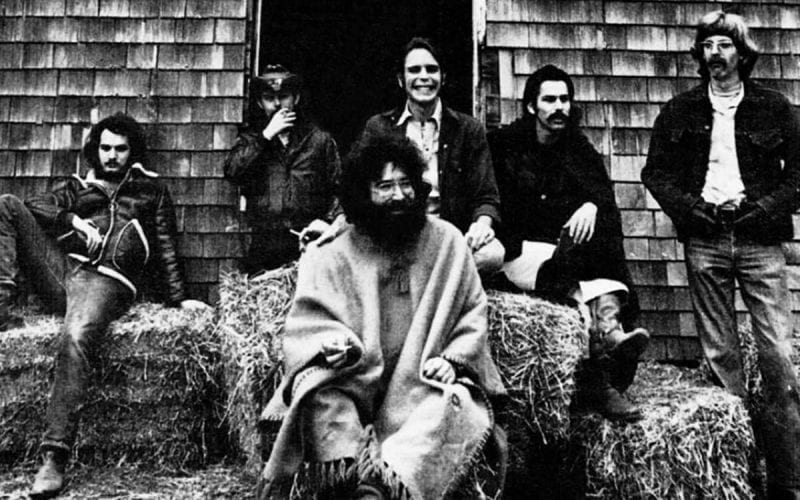

But in this documentary, the point is made over and over and over again that the soul and beauty of The Band is the fact that the magic was created equally, by all the members. It was a true collaboration, and one like no other.

In the film Bruce Springsteen states, “There is no band that emphasizes coming together and becoming greater than the sum of their parts. Simply the name, The Band, that was it.”

Similarly, Eric Clapton disbands Cream after he hears Music from Big Pink. He longs for a real band, a real brotherhood of collaboration where each member intertwines with one another, seamlessly, to make something bigger than all of them. He actually visits Woodstock where the band is living in the big pink house to see if they want a rhythm guitarist.

“Come on, let’s jam,” Clapton says excitedly.

They reply, “We don’t do that.” Clapton realizes, “Hey wait a minute, this is a songwriting outfit.”

When you see the history of The Band laid out, first as a back up band for Ronnie Hawkins, and then as the back up band for Bob Dylan, you begin to understand why there was never a true frontman in The Band. No one needed to step up to fill that role because there was already someone in place. It also gives us a glimpse into their natural formation of a group blending together as one, weaving their talents with no particular member standing out. This, obviously on purpose, as no one was going to upstage any star they were working for.

There is a funny part about them backing Bob Dylan. This was when Bob switched from the acoustic folk sound to going electric with a more rock feel. The story goes that Bob thought he’d have more power with a small group backing him and beefing up to electric instruments seemed like a natural evolution. In Bob’s documentary directed by Martin Scorsese, Bob states, “…It was electric but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s modernized just because it’s electric. Country music was electric too.”

Anyway, Robertson says, “…Although Bob thought this was a good idea, his fans didn’t think it was a good idea at all!” He talks about being booed at every show they played, both here and abroad. In the film Bob tells them, “…Whatever happens, don’t stop playing.” He also states the obvious. If the audience wishes he’d still be sticking with straight folk music, “…I don’t understand how fast they are buying up all the tickets!” Bob going electric and all the booing is, of course, legendary history. But it’s cool to see it on film because it shows you how brave it was for Bob to keep going, to keep following his vision, to keep leading the way. It also shows how “gallant” (per Bob), The Band was for sticking with him through all of it. It does get funny when Robertson states in so many words, “Let me get this straight, you rehearse, and then go out and play all of these songs, only to get booed every single night? Strange way to make a buck.”

When the guys decide to go on their own and live in a house together (the Big Pink house in Woodstock), they are able to stretch out both mentally and musically, they discover parts of themselves they never knew they had. Not only is each able to play multiple instruments, but they have a vocal blend that creates a totally unique sound.

And that’s how all of us discovered The Band and their music. Not unlike The Beatles, we knew the names of each player, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel, Rick Danko, Robbie Robertson, and Levon Helm, who arguably became the best known of the group for his lead vocals on some of their biggest songs. Indeed, in the film, Taj Mahal states, if there was an American Beatles, this, would be them.

One of the most fascinating things in this movie is a glimpse into the songwriting process of both Bob Dylan and Robbie Robertson. You see Bob come over to the pink house with his typewriter and some song ideas. The Band and he begin to play songs, some of which will become ideas for future famous Bob Dylan songs. But for now, a lot of the lyrics are just placeholders, dumb rhymes just stringing words together. In one, what will become, “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” there is a verse,

Now, look here dear Sue

You best feed the cats

The cats need feedin’

You’re the one to do it

Get your hat, feed the cats

You ain’t goin’ nowhere

Most of us are overwhelmed by the genius of Bob Dylan. Here we see a more mortal side–yep, just a bunch of words strung together in rhyme. Of course, he goes on to craft his songs into some of the greatest works ever written, but we discover he is human after all.

Robertson reminds us that the best way to write is to write what you know. But how to get that process started? Sometimes it’s as simple as looking into the sound hole of your Martin Guitar to see that it’s made in Nazareth, Pennsylvania. That’s how the song, “The Weight” began. “I pulled into Nazareth…” Then all of the characters he knew just came to him and the song fell naturally out of the guitar.

The film often returns to the overall theme of The Band becoming true brothers and the important role each played. And for me, this is where the film gets into trouble. While I appreciate Robbie Robertson’s individual history, if you keep telling me how great these guys were and how important they were, why don’t you tell us more about their lives, as well? If, The Band, is as great as you say, and deserves a true documentary, why not spend the time to enshrine each individual member?

Another thing that seems weird is the way the story is told by Robbie. He seems to be performing, over-acting, and disingenuous–I don’t buy it, I don’t believe him. Having his ex-wife Dominique tell a good part of the story adds credibility and is a nice touch, but again, we only get to hear their side of the story.

There was a big brouhaha some years ago about Robbie supposedly stealing all the publishing rights from the other Band members. The story goes that most of the other members were unaware that publishing credits were an extra source of income for a writer of a song, beyond touring and making a portion of record sales. When the album The Band came out, the guys were shocked to see their names only mentioned on one or two songs, while Robbie was credited on all 12. Perhaps Robbie wrote most of the lyrics but the guys felt they’d contributed so many great ideas that helped bring the songs to life that they deserved to be credited as well.

Trusting Robbie to do the right thing, working with their manager Albert Grossman at the time, proved to be a bad move. Robbie tried to gloss over the situation telling the guys that the money situation would all “even out” because much more money would be coming in via a recording studio that was going to be built by Albert in Bearsville, a hamlet in Woodstock. Robbie told them they would all be partners and share in the profits, but clearly, he knew what he was doing when he chose the final credits to be put on the album. And apparently, Levon’s caution that music business deals like this can ruin a band, and his appeal to Robbie that the guys should be treated equally as brothers, especially having gone through so much together, fell on deaf ears.

This part is not covered in the film, only that Levon and some of the others were apparently extremely upset and thought they deserved more of the writing credits, or at least, more of a fair share of the money made on the songs.

Robbie places someone in the film to explain that he, Robbie, wrote the songs and lessens the others’ contributions by defining them as only, “arrangements.” While this may be true on paper, we don’t get to hear Levon’s or any other Band member’s side of the story. Only that Levon and other members of The Band succumbed to alcoholism and heroin, and that led to Levon, “…not wanting to understand the truth.” The problem here is that there are much larger truths that aren’t covered in the film that no one seems to want to talk about.

First of all, Robbie may have written the basic words for the songs, but bringing songs to life is another story. The guys contributed so much to the melodies, chord changes, instrumentation, timing and tempos, that clearly, it took the whole Band to create these works. Remember Eric Clapton’s quote, what he saw was a songwriting “outfit,” a team effort.

Because I have friends who are close to the situation, I know some personal things that went down that not too many others know, and would not repeat in these pages. But suffice to say, there were more reasons other than business discrepancies for Levon Helm to be as mad as he was at Robbie Robertson. To whitewash all of this and simply blame the breakup on drugs and alcohol alone, painting Levon in a bad light, does a big disservice to Levon and all the other members of The Band. The worst part is, Levon, nor any of the others, aren’t there to defend themselves—we are getting the Robbie Robertson version of the story. He’s the one that made the film, so he’s the one who gets to tell it.

Perhaps Robertson needs to remember the story this way for his own peace of mind. Who knows, but somehow I came out of that movie feeling there was so much more to tell.

The story ends with footage from The Last Waltz. It’s stunning and it made me want to watch that movie again.

Despite my overall feelings I encourage you to see the film—it’s very worthwhile in so many ways.

This is a good time to repeat one of my all-time favorite quotes from Bruce Springsteen, “Trust the art, not the artist.” So it is, with this film.

Until next time, be smart and stay safe,

Rap~

© Paul Rappaport 2020

PS. In these challenging times I would like to offer what I see as some positive silver linings. The spread of the Coronavirus is forcing us to realize that we are, indeed, connected to one another globally and that we must all work together to solve the world’s larger problems. The front page of the New York times recently showed how pollution from human activity has rapidly dissipated due to our temporary shutdown—most notably over China. I imagine many people there are seeing blue skies and clouds for the first time in years. Perhaps they want to find a way to keep that.

I believe a shutdown of this magnitude forces us to stop and reflect more on the importance of community and family. Furthermore, we may make some future changes in the way we live based on what we learn from living differently. What if all this working from home proves to be beneficial. Perhaps we will find ourselves having to come into an office fewer days a week, reducing more traffic and pollution, and also retrieving some more personal time. Perhaps those that aren’t yet on board with trying to stem global warming will now believe more in science—science isn’t left wing or right wing, it has no political agenda, it’s just plain facts.

I am beginning to see people figuring out how to help one another through these difficult times. Yep, it’s pretty scary but sometimes tragedy on this level brings out the best in us human beings.