As soon as I hear Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band are going on tour, I begin to feel exhilarated. And all you Springsteen fans out there know why. Simply, in the world of rock music, there’s hardly anything more exciting or more uplifting than a Bruce Springsteen concert (save possibly for U2, who also possess the magic to warm our hearts and souls).

In the 1970’s Bruce Springsteen began to capture our hearts and souls with his purposeful songs, important sociological messages, and the just-plain-fun stories he told on stage. With incredibly moving performances, he transformed the biggest skeptics from a “show me” attitude to becoming religious zealots for the cause, helping to spread the word. Bruce Springsteen was your friend, your confidant—he stood for everything you did and he was your voice, speaking your truth, and speaking it to millions of others who felt just like you. For so many people around the word, he still does. Whether you’ve seen Bruce Springsteen perform a hundred times or it’s your first concert—you walk away feeling exalted, joyful, fulfilled, and with a smile planted on your face guaranteed to last for at least a month.

I started working with Bruce from the very beginning, with his first release on Columbia, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. I heard the album and loving the songs and imagery I was immediately attracted. But it was when my wife, Sharon, and I first saw him live at the Troubadour in 1973, that we realized Bruce was something extra special. Indeed, he was, he became the Elvis Presley of our time.

The Troubadour show was so rockin’ and so powerful the next morning I fired off a telex to the New York offices trying to capture all the excitement that everyone in the audience experienced that evening. Before the age of computers, we had a machine called a TWX (pronounced twix). You typed your message on one end and it came out on the receiving end just as you’d typed it. Bruce was renowned for playing a Fender Esquire model guitar, a bit rare and unusual for rockers—it was becoming a trademark for him. I made my poor assistant type the message in the shape of that guitar—only one word across for the headstock, perhaps two on the neck going down, and then following the curves of the body as I had traced it for her. Drove her nuts, but when the telex printed in New York it looked just like Bruce’s Fender Esquire and it blew minds.

Without a doubt, the phrase “The hardest working man in show business” describes Bruce Springsteen to a T. Of all the people I’ve ever worked with, I’ve never seen anyone who has his work ethic or is driven as much as he is. Not even close.

In the early days I used to enjoy watching him rehearse the band at sound-check. At around 2 or 3pm The E Street band would be on stage, and for large arena size shows, Bruce had an extra-long wire built for his guitar. It was easily 100 feet or longer as it stretched all the way from his amplifier on stage, down the center aisle, to the soundboard three quarters of the way back in the hall. Bruce was not only rehearsing the arrangements, he was also working on the sound at the same time, twisting knobs this way and that. I’d never seen such detailed attention to the control of the overall concert sound of a band by an artist like that before, and I’ve never seen it since.

A typical sound-check could last two hours, I remember one that lasted for three—that’s easily four or five times longer than any other artist or band I’ve ever witnessed at sound-check. Then the band would take a break, come back at eight o’clock and do a four-hour show. For anyone who’s ever seen Bruce, that’s four hours of constant athleticism, running up and down the stage, sliding on his knees, and being passed around the auditorium on his back by his loving fans.

After the show and a good 45-minute towel down, Bruce would come out of his dressing room to meet, shake hands, and talk with all the radio, press, and retail personnel, along with any lucky fans who happened to make it backstage. And this was no hurried affair. Bruce took the time to have a meaningful conversation with each person who was there. Sometimes, these backstage meet-and-greets could go on until one in the morning. Then, Bruce would finally head back to his hotel, get a few winks of sleep, get up and do the whole thing all over again—city, by city, by city.

In later years, at one concert after Bruce’s traditional three or four encores, he came backstage totally spent, dripping in sweat, yet looked from behind the stage curtain to see if any audience members were still standing and clapping. Columbia’s then head of sales, Tom Donnarumma, was backstage as well. He looked at Bruce quizzically and said something like, “Gee whiz Bruce, you’ve already done way more than anyone would ever expect of you. Are you actually thinking about going out there again??”

Bruce looked back at him and said in that raspy, after-a-four-hour-show Springsteen voice, “Donnarumma, I’m in the business of the unexpected.”

I was reading Bruce’s autobiography where he talks about not feeling the support of the Columbia label in his early years. This was certainly true of the higher-ups, but there were a few of us who understood right away that we were witnessing rock and roll history and we had strapped on our armor, held our shields high, and drew our swords to go out into the world like gladiators, to fight to the death to help make his career happen. In the beginning his four biggest fans were, the aforementioned Mike Pillot, Peter Philbin in A&R, Glen Brunman (nicknamed “Brahma”) from the publicity department, and myself.

It was hard for Bruce in the beginning because he had his own unique sound, was cutting his own musical groove. It’s usually those kinds of artists that have long careers but also take longer to get there, simply because it takes a while for people to really listen and absorb something new.

I was having an especially hard time on the west coast because most of the radio folks there just didn’t get it. I would hear complaints like, “He’s an east coast artist. He’s singing about giant Exxon signs—we don’t have Exxon here on the west coast.” I couldn’t believe they could hear Bruce’s incredible lyrics and only come away with that. Other folks had written him off as just a Bob Dylan copycat.

Despite all my hard work in trying to spread the word on what I was hearing and what I’d seen at the Troubadour, for Bruce’s first two albums, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J and The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle,only two disc-jockeys in southern California played any of his music, the aforementioned Steven Clean, and the “Burner” Mary Turner, both at KMET.

Mary especially took a liking to Bruce’s music, and one of my favorite memories is during the time of the second album convincing Bruce to do an interview with her. Bruce did hardly any interviews at all then, so this was going to be a big deal. When the “Lauren Bacall of Rock and Roll” (as I used to like to like think of her) put her stamp on a new act, it gave that artist instant credibility in Los Angeles. And Mary was now starting to play Bruce Springsteen at least once every night on her regular air-shift.

When I arrived at the station to meet Bruce, he was at the guard gate fuming. At the time Bruce didn’t dig the limousine rock star thing at all, he opted to drive himself everywhere. He’d pulled up in a rent-a-car wearing blue jeans and his patented rolled up flannel sleeve shirt, and the guard at the gate didn’t believe he was Bruce Springsteen.

The guard was a friend of mine and apologized but said that every other artist who ever came to KMET always pulled up in a limo, so he was skeptical. I tried to explain that to Bruce but he was really pissed.

“Get in,” he motioned for me to get into the passenger seat of the rent-a-car as he was going to drive us into the parking garage. Anger turned into road rage as Bruce started tearing around each corner of the garage as we worked our way up to the roof. The tires were squealing and sometimes I thought we were riding on two wheels as I held the arm rest for dear life. I remember thinking, ‘There’s a fifty-fifty chance that we could fly off the edge of the garage, have a bad accident, and die.’ And the only silver lining I could muster was, ‘Well, if we do die, at least I’ll go out with Bruce Springsteen and be remembered.’

When we got into the station, Bruce began to settle down a bit, and I popped a bottle of champagne to help loosen everyone up. I could tell he was still upset by the guard gate scene, so the champagne really helped. The best part of the interview was when Mary asked Bruce what his band did, while he was out doing all the public relations stuff.

“My band? My band is probably back at the Sunset Marquis catching all the television sets that the English bands are throwing out the window!”

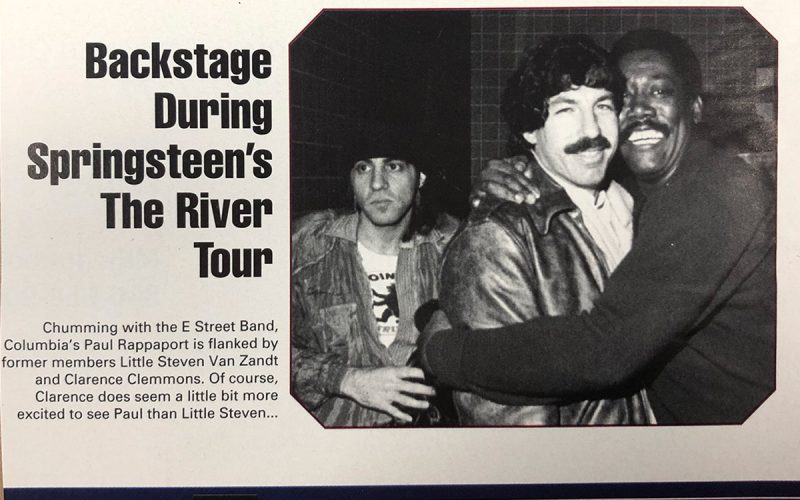

More Backstage Access:

Bruce Springsteen at The Roxy 7/7/78

The E-Street band were musicians like I’d never met before. They were somehow made of tougher stuff than most. I guess that came from playing all those long sets in bars together, and of course being from New Jersey and the New York area.

I had fun hanging out with them, mostly with drummer “Mighty Max” Weinberg and bassist Gary Talent, who were quite approachable. Clarence was a riot. I was once on the road with them for about a week. Every day of that week Clarence wore the same outfit—a light brown Mercedes mechanic jump suit. We were on a plane going to one of our final destinations when I finally got up the courage to ask him about it.

“Hey, Big Man, you’ve been wearing that exact same Mercedes jump suit for five days in a row now, pretty soon it might start to get a little funky—how long are you gonna wear it?

Clarence looked down at me with that big ol’ grin of his, and said, “I’m going to wear it, until someone (shooting an eye towards Bruce and manager Jon Landau) gets the idea.” The money was starting to roll in now, and the big man was looking for an upgrade.

Another soon-to-be friend, talented writer, Dave Marsh (you may have read some of his books), was on the road with the band as well, always carrying a little white typewriter and capturing all the rock history being made. On off hours, I used to love watching Marsh play pinball. A better pinball player I’ve never seen. He had a sixth sense, knew where the ball was going before it got there, and he banged the hell out of the pinball machines using powerful hip action, urging the ball, more like demanding the ball, to go where he wanted. Watching Marsh play pinball was a show in and of itself.

Those innocent days are always the best, when it’s all about the art and the mission, before the big money starts to roll in. After that happens, things get complicated, especially for the artist.

Once I found Bruce sitting on a curb with his fist curled under his chin like Rodin’s The Thinker statue. Bruce has a pretty even personality. But on that day, he looked unusually down, unhappy, bothered. I asked, “What’s wrong Boss?”

He looked up at me as if he’d had a lightbulb moment, “I just figured out that if I’m gonna make more than five hundred dollars a week, I’m gonna have more than five hundred-dollar-a-week problems!” I would go on to learn the same lesson.

When Bruce released The River album, he had a shot at having his first Top-40 hit single with “Hungry Heart.” In those days you could sell plenty of albums just off rock radio airplay alone, but if you also had a song that crossed over to the Top-40 format, you gained a whole lot of new fans. A one million selling album could multiply into a four million seller. I was backstage at a Cleveland show when I called the New York office who informed me that “Hungry Heart” was poised to be a big hit, it was going all the way.

After the show I walked up to Bruce excited, “Great news, you’re about to have big hit Top 40 record! Ka-ching, ka-ching!” He looked at me wide eyed and said, “Man that’s great. Cause you know my Vette? (Bruce had a cool looking blue Corvette at the time). I’ve been lookin’ for a set of wheels for it for the longest time!”

I said, “No, Bruce, I’m talkin’ about buying the whole Corvette factory kind of money!” He just looked at me like I was nuts, shook his head and walked away.

Now, he can buy the whole Corvette factory if he’d like. But it’s not the money that drives Bruce Springsteen, it’s the art, the craft of great songwriting. Once a young songwriter told me he’d lucked out and Bruce was helping him. He was at Bruce’s house asking about his work ethic. Bruce said something like, “You always have to be mashing the potatoes.” The songwriter countered, “Yeah, but it must be a lot easier now with all this money and wealth.” Bruce stared at him. “You’re not hearing me, all of that doesn’t matter. You always have to be mashing the potatoes!”

We can all watch Bruce mash those potatoes here in The States starting in February of next year. For now, here is a list of the first European dates just released.

Looking forward to a great summer. Surfing season is here!

Until next time, keep rockin’ kids!

Rap~

© Paul Rappaport 2002

More Backstage Access:

Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution