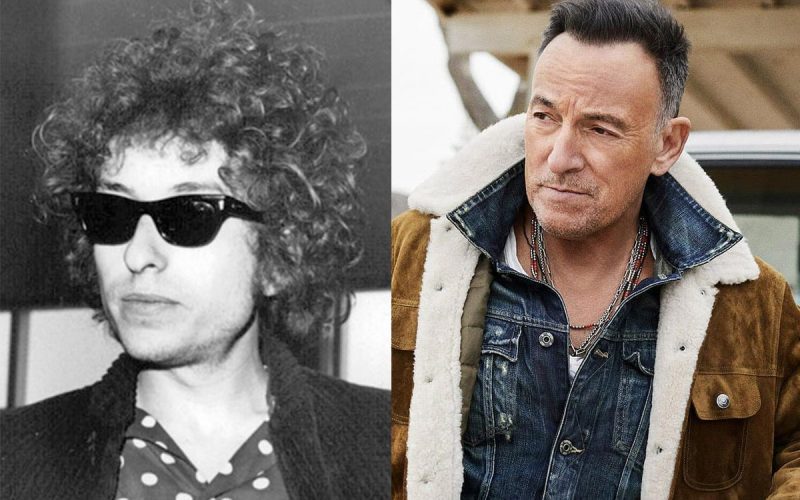

After recently reading about David Bowie’s estate selling his song catalog to Warner Chappell Music for approximately $250 million, I thought it was high time I cover the subject of why so many classic rock artists are rushing to sell their publishing. The music world, and the world in general, was shocked not too long ago when Bob Dylan decided to sell his songs to Universal Music Group for $400 million, and equally shocked when Bruce Springsteen sold his catalogue to Sony Music for somewhere upwards of $500 million.

Other recording artists started this trend before Bob and Bruce followed suit. It might be easier to understand why pop artists like Barry Manilow, Shakira, and Stevie Nicks would give up ownership of the songs they penned for some quick cash, but when it comes to songwriters like Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen — whose songs are arguably seen as works of art that helped shape the culture — it does make one scratch their head.

For those who don’t know, whenever a song is played on the radio, used in a TV commercial, or in a movie, the person or company who owns the publishing of that song collects a song performance royalty. Also, when selling vinyl LPs and CDs the writers of the songs also receive an extra cut from what is known as “mechanical” royalties. These are separate from the royalty one receives just for the sale of an album. Early on, a writer of a song received mechanical rates of approximately 2 cents per song. In the 1980’s that number rose to 5 cents per song for each song on every album sold. That number is now up to 9.1 cents.

At first you might think, ‘well that’s only pennies,’ but start doing the math and if you’ve penned 12 songs on an album, and you sell one million albums, that’s a lot of extra dough in your pocket.

In today’s world where streaming services like Spotify and Tidal are popular, artists are paid every time a song of theirs is clicked on. These services supposedly pay both mechanical and performance royalties, but it’s a bit murky how they define those terms because they can’t afford to pay a traditional mechanical royalty rate. And the amount of cents per song paid is an on-going battle between those services, the artists, and the record companies.

Not for the purpose of this article, but to illuminate further what’s going on for your edification, I want to explain how these membership-based streaming services divvy up the money. Yes, artists are receiving royalties, but not nearly at the same rate they do on album sales. At the end of the month these streaming services simply add up all the streams and pay out on who had the most streams, all the way down to had the least. That means “the flavor of the month” artists might rake in a lot of dough, taking an unfair share of the money right off the top, while those that fall below are left to divvy up the rest, and therefore are seriously underpaid.

At least, when album sales were the main method by which all mechanicals were paid out, an artist was guaranteed 5 to 9 cents per song on each album. They could always count on their loyal fans to buy a decent number of albums, and with 12 songs per album that could guarantee up to a half dollar or extra dollar per album. Even if you were just a midlevel artist selling two to five hundred thousand albums per release, you were making a living. Now, everyone is just thrown into a giant pile of other artists. Even if your loyal fans are clicking on your songs, if you’re not in the millions of streams at the top, not only are you are the victim of those streaming services’ low royalty pay rates, but there’s not enough money left over to split up in any meaningful fashion.

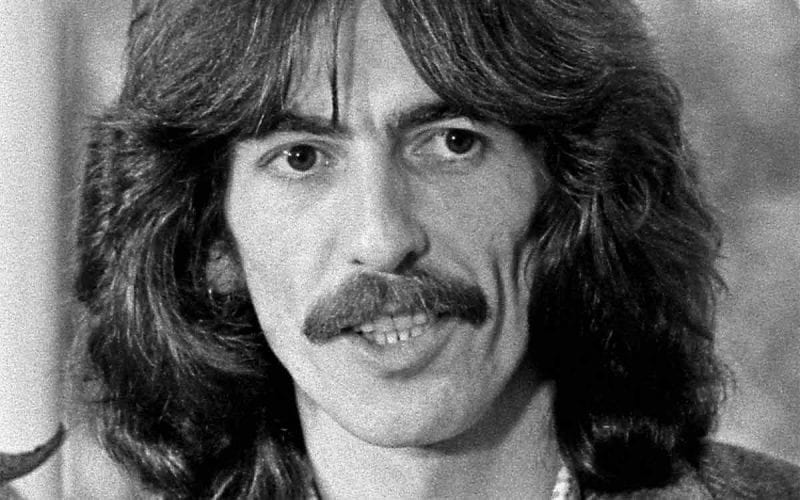

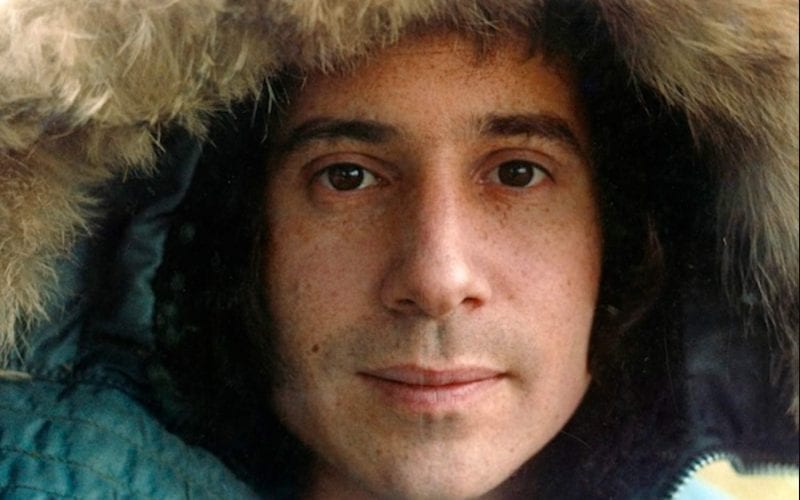

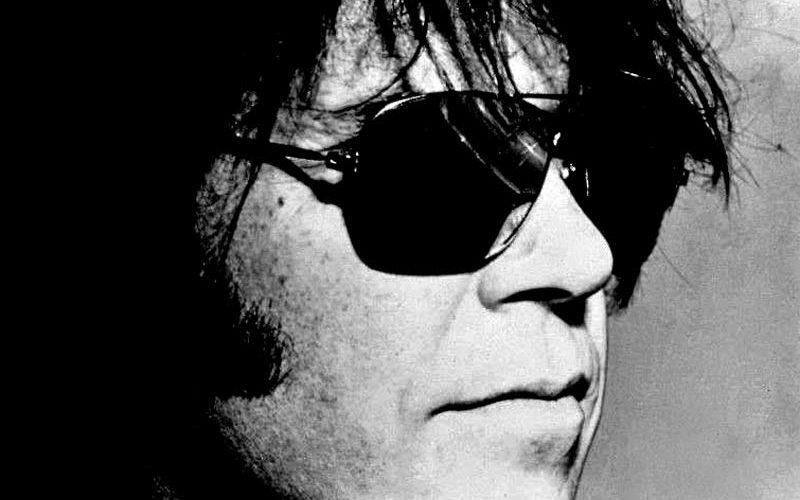

When songwriters like Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, and Neil Young hit the scene, writing songs with deep messages that affected the culture, the first word of advice they got was, “don’t sell your publishing.” This was for two reasons.

First, because of all the extra money you’d make off the song royalties, and second, because you would keep control of who would be able to use your songs. The latter was paramount to these artists, lest some of their most powerful messages could be misused or misconstrued playing behind a TV commercial for a car, sugar cereal, or toilet paper. If they didn’t like a particular movie, they wouldn’t grant the usage of one of their songs for it. Now, they are giving up that control.

And believe me, these artists know what these songs mean and they are very proud of them.

Bob Dylan once told me, “The problem with people meeting me is, they think they’re meeting the lyrics. I know how heavy these songs are, I wrote them. But I’m me, not the lyrics.” Once we were having dinner in the Village and Bob had just come back from Russia where they’d given him a big time poets award. He was so proud of that award, being recognized on the highest level for his poetry. I was trying to get him to focus on a video we needed to shoot and all he wanted to talk about was the art of Russian poets.

When Bruce Springsteen released the expanded box set for Darkness on the Edge of Town, it came with a facsimile of one of his early songwriting spiral notebooks. It allowed you to see his songwriting process. You could follow page after page how certain ideas, words, and phrases eventually became songs.

Once we were having dinner, and he was telling me about how he used to live in the back of a surfboard shop continually having to breathe in all the resin fumes. He said, “I finally got used to it. Hey, do think that may have affected my brain and my songwriting?!” I just laughed and replied, “Well if it did, it did it in a great way!”

On an interview album I did with Paul McCartney, Paul spoke of his own amazement regarding his songwriting capabilities. He said he often wondered about how that powerful gift came about from just a per chance magic combination of chromosomes and genes coming together during his conception, even before he was born!

More Backstage Access:

Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President – Plus Personal Insights on Gregg Allman & Bob Dylan

Before we delve into why these artists are now selling their most prized possessions, let me explain why buyers and investors are more interested than ever before to really get into the song publishing game.

Much of the music we know as classic rock, or classic in general, is imbedded into our minds and hearts, and has become a part of us and our overall culture. Because of this, the music has an intrinsic iconic value. These songs will be recognized for years to come, and they bring a familiar comfort factor. The price of oil, gold, etc. is always in flux depending on the politics of the day. But investors now view this music as a stable speculation that won’t change due to any market pressures or world politics. The value of these songs is a constant, and they believe this investment will pay off, and moreover, for a very long time.

Not too long ago two new companies, Hipgnosis and Prime Wave started buying up music rights from artists including Fleetwood Mac, Neil, Young, Shakira, John Lennon, and Dire Straits purely for this reason. Not to be outdone by these outsider startups, the record labels themselves quickly followed suit making deals with their own artists before their music got swallowed up by these two new publishing investment firms.

So, why now all-of-a-sudden, the change of heart by artists to sell their publishing, which in the past they held so close to their vests?

There is more than one answer. First off, none of these artists are getting any younger. Looking ahead to estate planning for their kids and grandkids, it’s a great way to ensure making life easier for them in the future and for more family members in the years to come.

Another reason is, it’s not clear that any of these artists’ children have the interest to take over their parent’s publishing company and be in charge of doling out money to rest the of the family as it comes in. Much easier to just split up a lump sum made available after the artist passes away.

And if big money is being offered now, who knows for sure if your songs will be worth the same amount in another 20 to 50 years?

Also, the stigma of “selling out” to “The Man” isn’t what it used to be. If any of these artists would have sold their music to a corporation in the 60’s or 70’s they would have lost all their credibility. And because of the cultural movement back then, it wouldn’t have even crossed their minds. But things are different now. Bob Dylan recently did a car commercial — he’s even selling his own brand of whiskey called “Heaven’s Door.”

And when dealing with reasons that concern only the money, believe it or not, some of these artists need the money. Living extravagant life styles, not all artists have managed their money well, saving for a rainy day. Especially because of the pandemic, with no touring available, large amounts of yearly income that these artists count on to keep their ships afloat has been nonexistent.

Lastly, if you’re going to sell, now is the time to do it. Not only for the value being placed on the songs at this time, but the Biden administration is working on changing the capital gains laws, so it’s important to get your sale in before your estate earnings may be more highly taxed. When you’re talking millions of dollars, that’s a lot of money.

But now we get to the existential part of the discussion. Who should really be in charge of the lives of these songs? Once you sell, you no longer have control of where these songs can be used.

What if a song, which means so much to so many, like “Born To Run,” is licensed away to be used in an Energizer Bunny battery TV commercial? What if “Blowin’ In The Wind” winds up as the background song to an air freshener advertisement? What if the classic Moody Blues 1964 hit “Go Now” gets used as the background music in a MiraLAX commercial!

What if a movie or documentary with a certain political bent that opposes an artist’s staunchest feelings is used or misused as part of that film’s message? Would it not cheapen the art, and perhaps change the intended meaning of a song to an unrecognizable degree? And someone younger, never having heard a particular song before, might only associate that song with the product being sold, never knowing its real meaning or historical importance it played in our society. It would be akin to walking into a McDonalds and seeing the Mona Lisa hanging under the menu sign.

For me, songs like Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ In The Wind,” “The Times They Are A’Changin’,” Bruce Springsteen’s “Born To Run,” “Thunder Road,” “Neil Young’s “Heart of Gold,” “Rockin’ in the Free World,” Paul Simon’s “America,” and so many more, should be held in the highest esteem. They are part of our history and belong in the Smithsonian Museum.

Having a real hard time with all of this, not wanting to believe my heroes would sell out, and in total frustration, I finally called a close friend who is a music business attorney and former manager to discuss all with him. He is always in the know and often has the inside track.

After me ranting for about a minute he finally calmed me down and explained that Bruce Springsteen’s deal, in particular, still gave him the approval power over certain “iconic” songs in his catalogue. He reasoned, if Bruce got this kind of deal, so did Bob and perhaps others as well.

I had to stop and think about that for a while. Well then, did these artists get the best of both worlds? Keeping approval power over some of their most important works while compromising and letting the rest go for a huge payout?

After a day thinking it over, I came to the conclusion that it’s a very slippery slope that these artists are traversing. Even if you have control over some of your work, these artists are so prolific that there are plenty of other songs that could get misused and abused by being placed into some damaging media. And don’t forget, it’s not just the songs, you’re also going to hear the artist’s voice, which will connote their endorsement of a particular product or message in a film or television series.

Now, you’re first thought may be, ‘well at least the songs and the artists will have some kind of protection if it is their record company who’s buying the music and has a stake in keeping the artists’ credibility solvent.’ And that may be true, up to a point.

But record companies are like any other kind of business, and now they are all owned by publicly traded corporations. At the end of the day, it’s the earnings and stockholders that matter, and money usually trumps any moral decisions.

But let’s even give them the benefit of the doubt. Let’s say they will do the right thing by the artists they represent. What happens if one day there is a terrible downturn in their business and they are forced to sell some assets? And suppose some of those assets they sell are song publishing rights? And what if those rights are sold to a corporation who has no feeling for the music or the artists who created it? What if a hedge fund buys a controlling share of that company’s stock?

It’s easy to see how quickly any kind of control could get out of hand and send some of the world’s most precious songs down an abysmal hole to be used in the most inappropriate of ways.

Can you imagine a Marjorie Taylor Greene type somewhere down the road using a Bruce Springsteen song as the background to their TV ad campaign?!! And not to pick sides, imagine a conservative country artist having a song of theirs being used in a political campaign for a congressional candidate who is a lightning rod for the far left like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. And neither the artist nor their family will be able to do anything about it. They will just have to sit there and watch themselves be aligned with someone whose politics they despise, their music being used to promote ideas and causes they may not believe in.

I have always felt that the record business was a perfect marriage of art and commerce. In this reporter’s opinion, when commerce takes over completely it can never be good for art.

Happy New Year to you all. Stay safe and maybe we’ll get lucky and this Covid thing will finally blow over in a meaningful way by spring or summer.

All the best,

Rap~

© Paul Rappaport 2022

More Backstage Access:

Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution